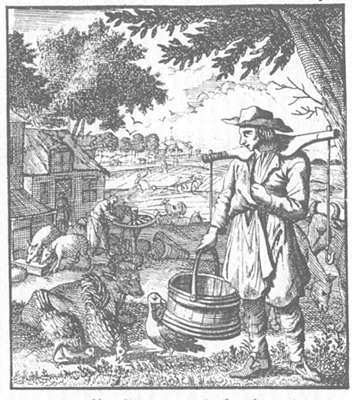

Almost every house in New Amsterdam had a kitchen garden and an orchard, even if only of a tree or two. The authorities encouraged the inhabitants to plant fruit and vegetables, so that they could feed themselves and their families. Some of the residents also had large farms or bouweries north of the wall.

Farming was a time-consuming occupation, entailing first the clearing of the land. Upriver, in Rensselaerswijck, early leases specified that farmers should cut down the trees on their land or “kill” them by de-barking them. New Netherland farmers were instructed to cut trees into logs, setting aside enough for fence rails and fuel, and to pile the rest in heaps to burn, using the ashes as fertilizer. Then underbrush had to be cut and burned, the root stubs cut, plowed, and harrowed, and the ground planted in wheat or rye, while sheep were confined to small portions of the field in turn, to eat the stubborn sprouts from the roots, until the field was finally subdued. The farmers were also to spread manure on their planted fields and keep them weeded.

Clearing the land before being able to farm it was highly labor intensive, and the most difficult part was getting the stumps and roots out of the ground. Much of the land worked by the tenants on the Rensselaerswijck patroonship had previously been cleared by Indians for their maize fields. But the Indians had left the roots in the ground, and so the Dutch farmers ploughed around the stumps and roots, leaving them in the ground, and thus diminishing the area suitable for planting. The difficulty in clearing the land and planting it was one reason for the upriver farmers often abandoning farming for better lives elsewhere. A document from Rensselaerswijck in1668 comments on the neglect of the land, the lack of fallowing it, the neglect of manuring it, and the weeds upon it. Farmland was so full of weeds and tares that it was difficult to sow seed on it.

An average-size farm in Rensselaerswijck in 1650 was about 57 acres. A century later, the average farm in New York was of 153 acres.

In New Amsterdam, farming was difficult not only because of the extent of forestation but also because of the thin topsoil.In the Out Ward and in the village of New Harlem at the northern end of Manhattan, the soil was richer. Later in the seventeenth century, many farmers left Manhattan for more fertile lands in the river valleys of New York and New Jersey. Still, agriculture was an important part of the economy in seventeenth-century New Netherland, where grains were the main product, planted first for subsistence, and then for profit. In 1656, Market Day was established in New Amsterdam, and every Saturday the country farmers in Brooklyn and western Long Island brought their produce to the city for sale. Later, in the 1680s, farmers shipped their produce down the Hudson River, or across it, by sloop. Farming methods vastly improved in the eighteenth century.

Adriaen van der Donck, A Description of New Netherland, ed. Charles T. Gehring and William A. Starna (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008).

Jan Folkerts, “Kiliaen van Rensselaer and Agricultural Productivity in His Domain: A New Look at the First Patroon and Rensselaerswijck Before 1664,” Nancy A. Zeller, ed., A Beautiful and Fruitful Place, Selected Rensselaerswijck Seminar Papers (Albany: New Netherland Publishing,1991), pp. 295-308.

Jan Folkerts, “The Failure of West India Company Farming on the Island of Manhattan,” de Halve Maen, 69 (Fall 1996), 3:47-52.

David Steven Cohen, “Dutch-American Farming: Crops, Livestock, and Equipment, 1623-1900,” New World Dutch Studies: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America, 1609-1776 (Albany: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), pp. 185-200.

The Etching Above is by:

Jan Luyken

Farmer (Landman)

1694