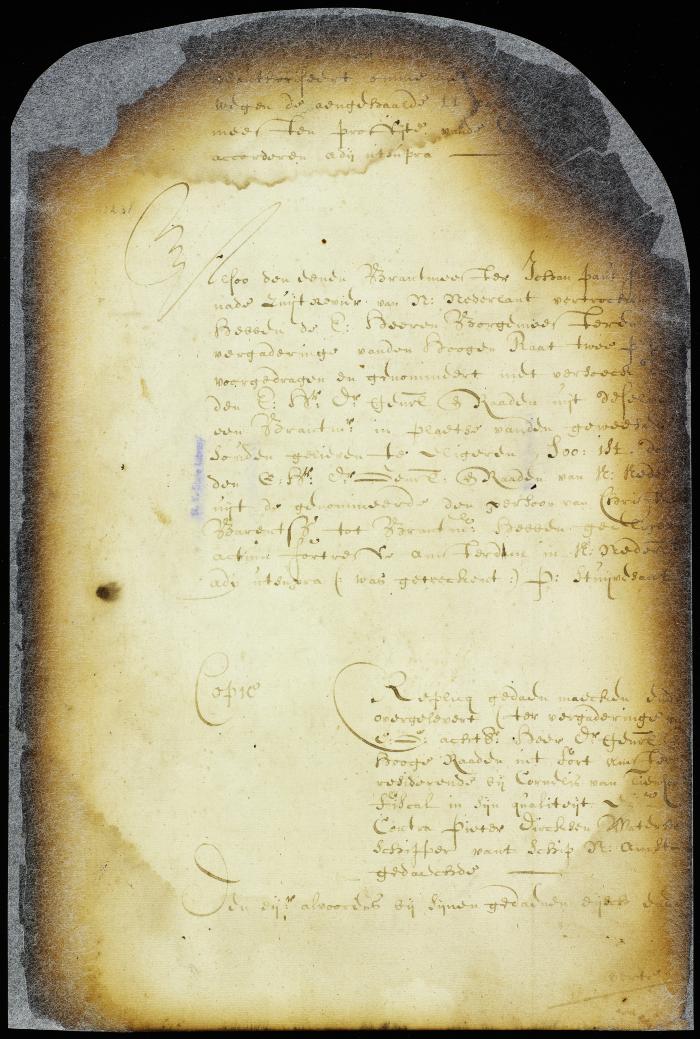

Copy

Response made and submitted (at the session of the honorable director general and high councilors residing at Fort Amsterdam) by Cornelis van Tienhoven, fiscal, in his capacity as plaintiff against Pieter Dircksen Waterhont, skipper of the ship N. Amsterdam, defendant.

The plaintiff, having persisted beforehand with his charge and consequent conclusion, says [ ] response to the false answers of the defendant that since this plaintiffs office ships no goods in any vessels without a permit or entry on the manifest, unless there are some smuggled goods that might be brought on board during the night, defrauding the plaintiff’s superiors and his masters’ privileges.[1] Also, the plaintiff requests proof that any peltries, tobacco or other goods have ever been loaded in any ships without a permit or without being registered. It is true that, upon the request of merchants, they have been permited for their convenience, accommodation, reduced effort, and expense take them from their houses and bring them to the usual place before the warehouse; and whereas they are taken on board before having given notification of the amount of weight of the tobacco, and the value of the peltries; and if Jacob Cohun had given notice that he intended to ship eleven barrels of tobacco, and if he had reported the weight as is customary, he would have been given permission as with others. With regard to the note of consent granted by the plaintiff dated 16 November 1655, it pertained only to the barks then at anchor, and the note by Adriaan van Tienhoven, dated the end of November, had no more meaning than [ ]

[one line lost]

ships, which also [ ] have been made, but [ ] which he was to ship some days thereafter [ ] Also, according to custom, no permits of the excise masters, as receivers of the duties, are to be valid no longer that the day upon which the same is granted; and if the merchant had obtained a permit, and it was inconvenient to ship anything on the same day, he is obliged to make notification again on the same day or at least on the next day; otherwise on such a permit so obtained, a whole or half of a ship could be loaded, and thus frustrate and cheat the lords of their duties.

That the skipper disavows the verbal warning made to him by the fiscal, not to load without a permit, is a false allegation because the plaintiff will undertake to prove that he warned the defendant in the aforesaid matter, and even if the fiscal had not given him a verbal warning, he remains and is still bound by his contract with the honorable Company not to load any goods without first taking them to the Company’s warehouse, and to be presented a document thereof. It is strange that the defendant dares to deny having been given a warning by the plaintiff. On the contrary it is evident that on the 16th of November, when the barks [ ] that the plaintiff [ ] came on board in order, according to [ J, to see what the barks [ ] on board; not finding the skipper on board very early in the morning, he ordered the pilot and supercargo not to take on any tobacco or other goods without paying the duty and presenting the document thereof; and that they were to inform their skipper thereof. Their skipper had gone ashore, so they said, in order to inform the plaintiff, which seemed to be true, especially since the defendant informed the lord general thereof on shore (because of the absence of the fiscal) that he did not intend to accept one barrel more than was granted on the plaintiff’s certificate of consent, dated 16 November. From such unnecessary claims it appears evident that the defendant was well acquainted that no goods were allowed to be loaded without consent; let alone so very early in the morning near by Smiths Valey, far from the usual loading place and the Company’s warehouse. Also, there is to be taken into consideration that the tobacco discovered by the plaintiff had not been weighed, much less reported; especially since the Jew himself said that he did not know how much the goods weighed, and that, after they had been removed from the ship, they were weighed on the scales at the request of the Jew, released on bail, and shipped with permission. The plaintiff requests justice so that his lords and masters will not suffer any perceivable loss under similar pretexts. (Dated:) 18 January 1656, New Amsterdam.

Rights: This translation is provided for education and research purposes, courtesy of the New York State Library Manuscripts and Special Collections, Mutual Cultural Heritage Project. Rights may be reserved. Responsibility for securing permissions to distribute, publish, reproduce or other use rest with the user. For additional information see our Copyright and Use Statement Source: New York State Archives. New Netherland. Council. Dutch colonial council minutes, 1638-1665. Series A1809. Volume 6.