The portrait above is by Bartholomeus vander Helst " Portrait of a Man" 1647. It is used as a placeholder until a verified portrait of Asser can be identified.

| Spouse | Marriage |

|---|---|

| Miriam Levy (ID: 1609,000,187) | 1,660,117 - 1609,000,187 Levy - Israel |

For more related reading see: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/US-Israel/amsterdam.html http://www.amazon.com/Exploring-Historic-Dutch-New-York/dp/0486486370

For an exhibit from the American Sephardi Federation on the 23 Jews who left Recife for New Amsterdam, please see the American Sephardic Federation. To access the finding aid to the collection of his inventory papers at the Center for Jewish History: https://archives.cjh.org/repositories/3/resources/348 . Noah Gelfand's article on Asser Levy breaks new ground on the subject of his arrival in Manhattan.

Asser Levy (?- 1680), also known as Asher Levy, was the spokesperson of the first Jewish settlement in the United States. There were the twenty-three Jews who left Recife, Brazil for New Amsterdam (now known as New York City) in 1654 on board the French ship Sainte Catherine. Levy, along with Jacob Barsimson, was an advocate for the small Jewish community in New Amsterdam. He fought for the rights of the Jews, especially to bear arms, and won the right for the Jews to be on guard duty instead of paying a special tax. 1 Levy was also one of the first licensed butchers in the colony. In 1657 the burgher right was made absolutely essential for certain trading privileges, and within two days of a notice to that effect Asser Levy appeared in court requesting to be admitted as a burgher. The officials expressed their surprise atsuch a request. The record reads: "The Jew claims that such ought not to be refused him as he keeps watch and ward like other burghers, showing a burgher's certificate from the city of Amsterdam that the Jew is a burgher there." The application was denied, but Levy at once brought the matter before Stuyvesant and the council, which, mindful of the previous experience, ordered that Jews should be admitted as burghers (April 21, 1657). 2 More recent scholarship describes Asser Levy as follows: Asser Levy, probably from Vilnius, Lithuania, was perhaps the first Jew to arrive in New Amsterdam, a matter of weeks before a group of 23 Sephardic Jews arrived as refugees from the former Dutch colony of Brazil. He worked variously as a merchant, butcher, and real estate entrepreneur over the next 30 years and played a major role in the struggles to obtain equal protection under prevailing law for himself and his coreligionists. 3 For more info see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asser_Levy

There is also a book on the migration of the first Jews in New Netherland: http://www.amazon.com/Time-Planting-Migration-1654-1820-America/dp/0801851203

Asser Levy’s long road to Manhattan began in Vilna, his birthplace in seventeenth-century Poland. He moved to Schwelm, a town in the Ruhr Valley near Dusseldorf, probably as a result of the Cossack pogroms, and then travelled to Amsterdam, where like so many others, he learned about new opportunities in New Amsterdam. Together with two other Ashkenazi Jews, Jacob Barsimon and Solomon Pietersen, he sailed to Manhattan on board the Peereboom, (Pear Tree) on 22 August 1654. Arriving as the bonfires celebrating the end of the First Anglo-Dutch War were burning, Levy and his fellow passengers were in the vanguard of a new surge in migration to New Netherland that would climax in the years before the English conquest in 1664.

Within two weeks of Levy’s arrival, twenty-three Sephardic Jews came to New Amsterdam having fled Pernambuco, the Dutch colony in Brazil recently lost to the Portuguese. These refugees had few resources available to them and faced immediate discrimination by the Director General of New Netherland. Writing to his West India Company superiors, Petrus Stuyvesant claimed that the new Jewish refugees were “very repugnant” to the general population, representatives of a “deceitful race” that should not be allowed to “infect and trouble” the new colony. In their response, West India Company officials agreed with Stuyvesant’s characterizations but ordered him to allow Jews to remain in New Netherland and be permitted to trade and travel like other residents, provided their poor did not become a burden on the colony. Undoubtedly, the WIC directors were influenced by Amsterdam’s Sephardic Jewish community, which reminded them of Jewish service to the company in Brazil, and of their continued financial commitment to the company.

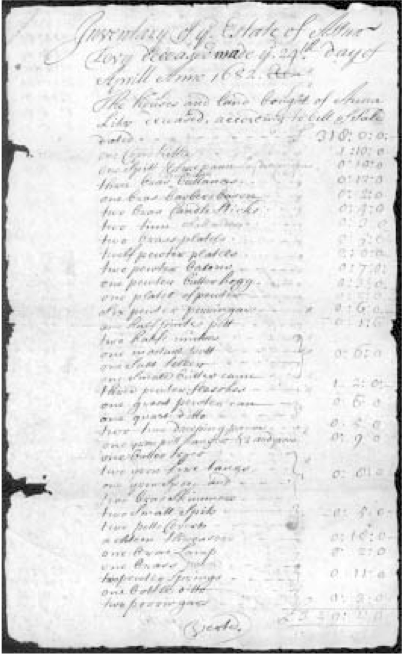

A list of Asser Levy’s possessions

In spite of the WIC directive, both Ashkenazim and Sephardim found New Amsterdam a difficult place in which to live. Although their religious practice was tolerated – like other minority religious groups, they could worship in private – Jews faced attempts to curtail their political and civil rights. Asser Levy and others fought back, using the one method available to them – petitioning the government – to challenge restrictions on their ability to own real estate, to trade freely throughout New Netherland, and to participate in the burgher guard. Initially, their efforts met with little success. When Levy and Jacob Barsimon protested the tax levied against Jews to support the local militia, Stuyvesant and his council informed them that, if they could not afford the tax, they were given permission “to depart whenever and wherever they please.”

The most significant attempt to limit Jews’ civic rights was the effort to prevent Jews from becoming official citizens or burghers of New Amsterdam. As commercial opportunities increased after 1654, New Amsterdam’s merchant leaders saw the biggest threat to their potential prosperity coming from itinerant traders, nonresident “peddlers” who did not contribute to New Amsterdam’s growing community. According to the magistrates, “Jews and other foreigners” drained the benefits of economic growth by trading at cheaper prices and undermining the value of wampum, the local currency. In response to the magistrate’s requests, the WIC granted the “burgher right” to residents of Manhattan, giving city officials complete control over who could become citizens. Perhaps sensing the anti-Semitic feelings of Stuyvesant, the magistrates chose to deny the burgher right to Jews. Once again, Asser Levy led the Jewish challenge. He was the first to petition the municipal court, formally requesting the burgher right on 11 April 1657. He claimed that citizenship should not be refused him because he kept watch like the other residents of Manhattan and that he previously had been a burgher of Amsterdam. The city court denied his petition and referred the matter to Stuyvesant and his council. Other Jews like Salvador d’Andrada soon followed Levy’s example, adding their petitions to his. Stuyvesant reluctantly agreed a few days, later and New Amsterdam’s Jews were admitted as city burghers.

In spite of their victory, Jews began to leave New Amsterdam so that by 1663, most had gone – but not Asser Levy. Levy took full advantage of his newly guaranteed rights as a municipal citizen and began a varied, wide-ranging career as a butcher, merchant, and land speculator. Within three years gaining the burgher right, Levy was the only Jew out of six applicants for the position of “sworn butcher” of the city. In his application, Levy requested that he not be required to kill hogs since it was against his religion. This time, the magistrates immediately approved his request and supported the limitations required by his faith. By the 1670s, he built a large slaughterhouse with his partner at the south end of Wall Street and purchased additional properties in Manhattan. Levy also continued his commercial activities – maintaining his relationship with business partners in Amsterdam, travelling to Germany in search of new markets, and developing his own connections in Fort Orange / Albany, Esopus, and Long Island.

When the English took over New Netherland in 1664, Levy became a denizen of the English empire, status that supported his position as a merchant. Over the next two decades, Levy traded grain, flour, salt, peas, and tobacco in exchange for a variety of imported manufactured goods. When he died in 1682, he left a considerable estate to which more than 400 New Yorkers were indebted.

Asser Levy’s persistence, assertiveness, and determination gave him a successful life in early New York. As the first permanent Jewish resident of early New York, his life and career served as a model and inspiration to the next group of Jewish immigrants who would arrive in the late 17th century.

Documents below also show that Asser Levy held property in Beverwyck in 1664.

The Diary of Asser Levy: First Jewish Citizen of New York by Daniella Weil is a fictionalized account of his life as a young man, and presents an alternate theory regarding his arrival in New Amsterdam and his introduction to his wife Miriam. The author researched extensively in the US and abroad. Research on this subject is continuing, and the NAHC remains dedicated to assisting writers inspired by the Dutch Colonial Period.

The New Amsterdam History Center's presentation on Religious Tolerance is particularly interesting as it relates to Asser Levy and the Jews of New Amsterdam.

1 wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asser_Levy 2 http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=310&letter=L

2. The portrait above is by Bartholomeus vander Helst " Portrait of a Man" 1647. It is used as a placeholder until a verified portrait of Asser can be identified.

3 Museum of the City of New York: Amsterdam, New Amsterdam exhibit 2009 description from item: Deed by which Asser Levy purchased property from Jacob Young, 5 September 1677; 34.86

Wessel Evertsen built house for Asser Levy

(left no descendants)